It’s a common sight in San Jose: an overgrown tree that looks like it’s taking over the yard. The immediate temptation is to give it a hard, aggressive trim to get it back under control. But this impulse, while well-intentioned, is often the first step toward creating a much bigger, more dangerous problem down the road.

The truth is, proper pruning is a science. It’s not just about cosmetic shaping; it’s about understanding and working with a tree’s biology to ensure its long-term structural health and stability, especially in the face of our region’s atmospheric rivers.

Why Some Tree Trimming Does More Harm Than Good

Many homeowners ask us, “Can’t you just trim more to make the tree safer?” or “Isn’t cutting it back hard the best way to control it?” These misconceptions stem from the belief that any trimming is beneficial.

However, recent insights show that improper trimming can drastically shorten a tree’s life and even increase hazard risk. When crews over-trim or make the wrong kinds of cuts, they’re not just removing branches; they’re inflicting massive wounds that leave the tree vulnerable to decay and disease. This is, without a doubt, one of the most common ways homeowners unknowingly introduce trimming mistakes that kill healthy trees.

The Problem With Aggressive Cutting

What this actually means for you is that tree trimming is about structural biology, not just cosmetic shaping. Correct cuts maintain load distribution, prevent decay, and protect long-term stability. Over-thinning or topping removes a tree’s ability to sustain itself, making it more dangerous in high-wind San Jose storm cycles.

Think of tree trimming like surgery. A skilled surgeon makes precise, minimal incisions to improve a patient’s health. A butcher, on the other hand, leaves behind a mess that causes more problems than it solves. It’s the same with your trees.

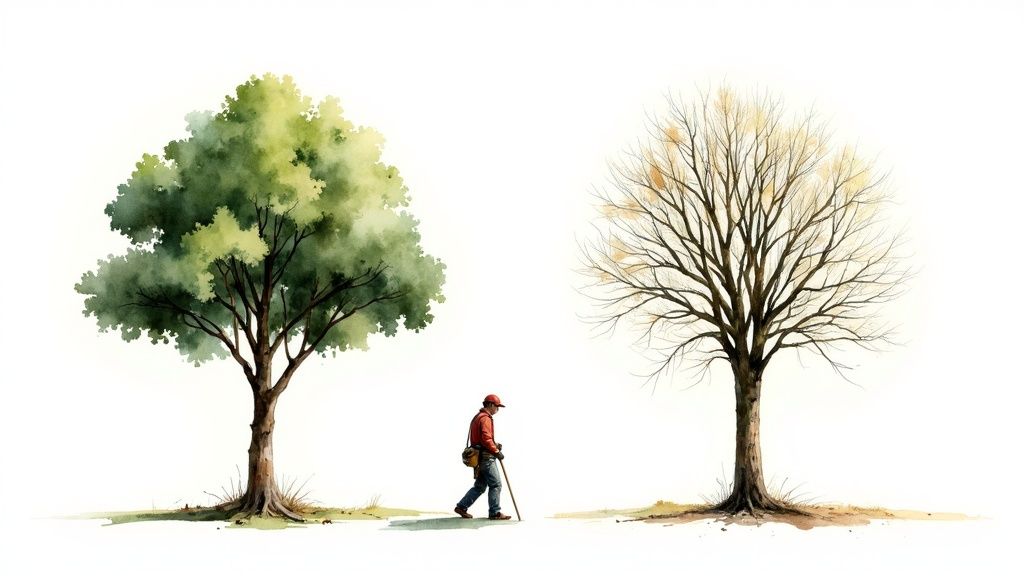

Healthy Pruning vs. Harmful Trimming At a Glance

Sometimes, seeing the difference side-by-side makes it click. Use this quick reference to instantly spot the difference between professional techniques that promote tree health and dangerous mistakes that cause long-term damage.

| Practice | Beneficial Pruning (The Right Way) | Harmful Trimming (The Wrong Way) | Long-Term Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Branch Removal | Makes clean cuts just outside the branch collar to promote healing. | Cuts flush to the trunk or leaves long stubs, preventing wound closure. | The right way leads to a healthy, sealed wound. The wrong way invites decay deep into the trunk. |

| Thinning | Selectively removes 15-20% of live interior branches to improve light and air flow. | Removes too many interior branches (“lion-tailing”) or over-thins the canopy. | Correct thinning creates a stable structure. Over-thinning weakens branches and leads to sunburn. |

| Size Reduction | Uses reduction cuts back to a lateral branch that is at least 1/3 the diameter of the removed stem. | “Tops” the tree by indiscriminately shearing off the top, ignoring tree structure. | Proper reduction maintains natural form and strength. Topping creates weak, hazardous regrowth. |

| Deadwooding | Removes dead, dying, or diseased branches to improve health and safety. | Ignores dead branches, leaving them to rot and become entry points for pests. | Removing deadwood eliminates hazards and disease. Leaving it encourages further decay and instability. |

Understanding these distinctions is the first step toward becoming a better steward for your trees.

Understanding a Tree’s Natural Defense System

Every branch connects to the trunk at a swollen, slightly raised area called the branch collar. This little spot is a biological marvel—it’s packed with specialized cells designed to seal off a wound after a branch is shed or correctly pruned.

When a cut is made too close to the trunk (a flush cut) or a long stub is left behind, this brilliant natural defense system is completely bypassed.

This one mistake opens the door for a host of problems:

- Decay and Rot: Fungi and bacteria have a direct pathway into the heart of the tree.

- Weak Regrowth: The tree panics and sends out a flurry of fast-growing, weakly attached shoots near the wound. These are prone to breaking off.

- Increased Instability: A compromised trunk and weak new growth can’t handle the high winds of an atmospheric river, turning a once-healthy tree into a serious liability.

Knowing how to cut is just as important as knowing when. In fact, timing your pruning can make all the difference, which you can read more about in our guide on tree trimming timing every South Bay homeowner must know. Combining the right techniques with the right timing is the foundation for avoiding these fatal mistakes.

The Unseen Damage of Tree Topping

Let me be blunt: topping is not pruning. It’s butchery. I’ve seen it countless times across the South Bay—a beautiful, mature oak or redwood reduced to a collection of ugly stubs. This practice is probably the single most destructive mistake a homeowner can make, turning a beautiful landscape feature into a ticking time bomb.

People often top their trees thinking it’s a quick fix for a tree that’s gotten too tall or seems like a storm risk. The irony is, it does the exact opposite. It creates a temporary illusion of safety that gives way to a far more dangerous situation down the road.

The Biological Aftermath of a Bad Haircut

When you top a tree, you throw its entire biological system into shock. Those massive, flat cuts left behind are too large for the tree to ever heal properly. Think of them as giant, open wounds that create a perfect entryway for decay, fungi, and boring insects to move in.

These invaders don’t just stay put. They travel down the branches and into the main trunk, rotting the tree from the inside out. This internal decay is often invisible until it’s too late, completely undermining the tree’s structural integrity. Topping is the root cause of many sudden tree failures I’ve been called out to assess years after the damage was done.

Pro Tip: Topping a tree is like performing surgery with a chainsaw instead of a scalpel. The trauma is immense, and the long-term consequences are severe, leading to a weak, unstable, and ultimately hazardous tree.

How Topping Creates Weak, Unsafe Growth

A topped tree panics. It goes into survival mode. To make up for the catastrophic loss of its leaves—the tree’s food factory—it desperately pushes out a dense cluster of thin, flimsy shoots right below the cuts. These are known as water sprouts.

Don’t mistake this for healthy new growth; it’s a stress response. Unlike strong, natural branches that are deeply anchored in the tree’s structure, these sprouts are barely attached to the outer layer of wood. This leads to a few serious problems:

- Weak Attachment Points: These new shoots are notorious for snapping off in high winds, exactly the kind we get during San Jose’s atmospheric river events.

- A Dense, Unstable Canopy: As the sprouts grow, they form a thick, bushy crown that acts like a sail in the wind, putting immense stress on the already rotting stubs.

- Accelerated Decline: The tree burns through its energy reserves to produce this weak growth, essentially starving its root system and speeding up its death.

This vicious cycle of decay and weak regrowth is precisely why topping is one of the most serious trimming mistakes that kill healthy trees. It’s a direct cause of preventable property damage and accidents.

An Open Invitation for Pests and Disease

Those large, flat wounds from topping are slow to close, if they ever do. The exposed, moist wood becomes an ideal breeding ground for pests and diseases to establish a foothold. Once an infestation starts, it can be incredibly difficult and expensive for a homeowner to fix.

For South Bay homeowners, this means a topped tree is far more vulnerable to local troublemakers like oak wilt, fire blight, and various boring beetles. Proper pruning is your best defense. Instead of topping, a professional arborist uses a technique called crown reduction. This involves carefully shortening branches back to a healthy, live lateral limb, which preserves the tree’s natural form and strength. It’s the right way to manage a tree’s size safely.

For a deeper dive into protecting your trees, check out our guide to pest and disease management of trees and plants.

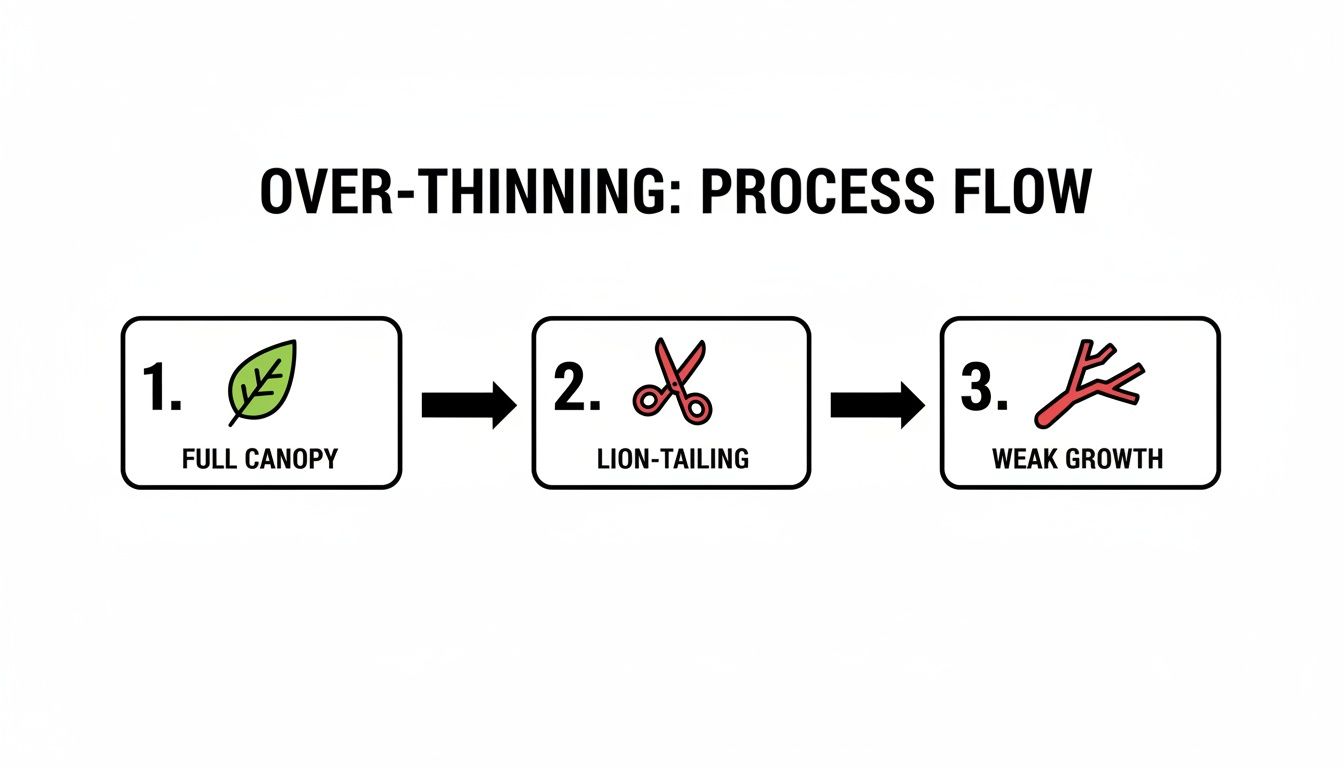

How Over-Thinning Starves Your Tree

When it comes to tree trimming, less is often more. It’s tempting to want a perfectly clean, manicured look, but aggressively thinning out a tree’s inner canopy can do far more harm than good. I’ve seen it countless times across the South Bay: a well-meaning homeowner or an unqualified trimmer strips out all the small, interior branches, leaving tufts of leaves only at the very ends of the limbs.

This practice has a name: lion-tailing. And while it might look tidy for a moment, it’s a slow death sentence for the tree.

Think of a tree’s leaves as its power source. They’re the solar panels that capture sunlight and create the energy needed for everything—from growing taller to fighting off diseases. When you lion-tail a tree, you’re essentially ripping out most of its energy production, putting it on a starvation diet.

The Panic Response: Weak Shoots and Snapping Limbs

A tree suddenly robbed of its food source doesn’t just give up; it panics. In a desperate attempt to survive, it forces out a flurry of weak, spindly shoots right from the bark of the now-bare limbs. These are called epicormic sprouts, and they are nothing like real branches. They are flimsy, poorly attached, and snap off with the slightest provocation.

Worse yet, lion-tailing completely ruins the tree’s structural integrity. A healthy tree has its foliage spread out, which helps it absorb and buffer the force of the wind. By pushing all the weight to the tips of the branches, you create a dangerous “ball-and-chain” effect. Every gust of wind puts immense leverage on the limbs, making them incredibly prone to snapping during a big San Jose storm.

Pro Tip: Imagine a well-built bridge with supports all along its length. Over-thinning is like knocking out all the internal trusses and leaving the entire load to be held by the endpoints. It’s a textbook recipe for failure.

Sunburn is a Real Thing for Trees

Here in the South Bay, our intense summer sun is no joke. A tree’s inner canopy isn’t just for looks; it’s a vital layer of protection, shading the sensitive bark on the main branches and trunk. Strip that away, and you expose the bark to direct, harsh sunlight.

The result is a condition called sunscald—a nasty sunburn for your tree. It kills the living tissue right under the bark, causing it to crack, peel, and die back. Those dead patches become wide-open doors for boring insects and fungal diseases to move in, sending the tree into a rapid decline.

The 25% Rule What a Pro Knows

This is precisely why a certified arborist will never lion-tail a tree. The professional standard, backed by decades of research, is simple: never remove more than 25% of a tree’s live foliage in a single year. For older or stressed trees, we’re even more conservative, often sticking to just 10-15%. This careful approach allows us to improve the tree’s structure and health without compromising its ability to feed and protect itself.

The danger here isn’t just to the tree. Trimming unstable, weakened trees is incredibly hazardous work. Following established safety protocols like the ANSI A300 standards isn’t just about doing a good job; it’s about keeping people safe.

Making Cuts That Heal Instead of Harm

The difference between a healthy, thriving tree and one slowly dying often comes down to just a few inches of wood. A proper pruning cut is a precise, almost surgical action designed to work with the tree’s natural healing process. It’s a detail many well-meaning homeowners and unqualified trimmers get disastrously wrong.

The secret to a good cut is understanding a small but critical part of the tree’s anatomy: the branch collar. This is that slightly swollen, often wrinkly area where a branch meets the trunk. Think of it as the tree’s dedicated healing zone, packed with specialized cells ready to seal off a wound and prevent decay from ever reaching the main trunk.

Flush Cuts and Stubs: The Two Big Mistakes

I see two common cutting errors all the time, and they both completely sabotage this natural defense system. These mistakes create long-term problems that can eventually kill a beautiful tree.

- Flush Cuts: This is when a branch is sawn off right against the trunk. It might look “clean” to the untrained eye, but this cut completely removes the branch collar. Without it, the tree has no way to form a protective callus over the wound. You’re left with a large, open injury that’s a direct gateway for rot and disease.

- Leaving Long Stubs: The opposite mistake is just as bad. Cutting a branch too far from the trunk leaves a dead stub. The tree’s healing cells in the branch collar are too far away to close the wound, so the stub simply dies and starts to rot. It’s an open invitation for pests and decay to move in.

Both of these are prime examples of bad pruning. Learning the correct technique is one of the most important things to know if you want to understand how to avoid the trimming mistakes that kill healthy trees. A good cut preserves the collar without leaving a stub, allowing the tree to compartmentalize and heal cleanly.

This diagram shows another common mistake, called “lion-tailing,” which strips a tree’s inner branches and leaves foliage only at the tips.

When you strip the inner canopy like this, you force the tree into a stressed state. It responds by producing weak, leggy growth that’s far more likely to snap in a storm.

The Correct Three-Cut Method for Larger Limbs

For any branch larger than an inch or two in diameter, just lopping it off in one go is a recipe for disaster. The weight of the falling branch will almost certainly tear a long strip of bark right off the trunk, creating a massive, ragged wound that will never heal properly.

To prevent this, we use a simple but crucial three-cut technique. It’s a non-negotiable part of safe and effective pruning.

First, make an undercut. About 6-12 inches from the trunk, make your first cut from the bottom of the branch, going about one-third of the way through. This little cut is a safety stop—it prevents the bark from tearing down the trunk when the branch falls.

Next is the relief cut. Move a few inches further out from your first cut and make your second cut from the top, sawing all the way through the branch. The limb will break away cleanly between these two cuts without damaging the trunk.

Finally, you’re left with a small, manageable stub. Now you can make your final cut. Make this last, precise cut just outside the branch bark collar, angling it slightly away from the trunk. This is the cut that matters most for the tree’s long-term health.

Safety Note: By following this three-step process, you remove the limb’s weight before making the critical final cut. This simple technique prevents tearing and gives the tree the best possible chance to seal the wound and defend itself against decay.

This isn’t just about making things look tidy; it’s about respecting the tree’s biology. Every single cut is an opportunity to either boost its health or inflict a wound that could lead to its eventual demise. Getting this one detail right is the foundation of responsible tree care.

Adopting a Minimal Effective Pruning Standard

After seeing what not to do, what’s the right way to prune a tree? The best philosophy is “minimal effective pruning.” This isn’t about hacking a tree into a new shape. It’s about making a few smart, strategic cuts that set it up for a long, healthy, and safe life.

The goal is to enhance the tree, not fight it. We’re working with its natural biology. By trimming only what’s absolutely necessary, we help the tree conserve energy and maintain the structural integrity it’s spent years building.

✔ Remove only what improves structure or safety.

Structural pruning is the key, especially for young trees. Think of it as guiding a tree’s growth to create a strong, stable framework that will hold up for decades. A little proactive care now prevents a world of problems later on, like weak branches snapping off in a storm—something we see all too often in the San Jose area.

Here’s your priority list for what needs to come off:

- Dead, Damaged, or Dying Wood: This is non-negotiable. Dead branches are a falling hazard and an open invitation for pests and rot. They should always be the first to go.

- Diseased Limbs: If you spot signs of an infection like fire blight or oak wilt, cutting out those branches can literally save the tree by stopping the pathogen in its tracks.

- Crossing and Rubbing Branches: When two branches grind against each other, they create wounds. These raw spots are a gateway for disease. The best move is to remove one of them—usually the smaller or weaker of the two.

✔ Avoid topping at all costs.

For most tree species, you want one single, dominant trunk growing straight up. This is the tree’s backbone. Pruning helps prevent the tree from developing two competing “leaders” (called co-dominant stems) which create a weak fork that’s incredibly prone to splitting. Topping destroys this natural structure.

A professional will use subordination cuts to slow down an overgrown branch or reduction cuts to manage a tree’s size, preserving its natural form and strength. These techniques are infinitely better and safer than topping.

✔ Use proper branch collar cuts.

As discussed, every final cut must be made just outside the branch collar. This respects the tree’s anatomy and allows it to heal properly, preventing decay from entering the trunk.

✔ Consult an arborist for complex issues.

Anyone can handle snipping a few small dead twigs. But some jobs are absolutely not DIY. Any time you’re dealing with co-dominant stems, large limbs, or storm-compromised trees, the risks skyrocket.

That’s when it’s time to find a qualified arborist near you. Certified expertise is required for complex pruning decisions, disease assessment, or hazard mitigation. A professional has the training to assess a tree’s structure and make cuts that protect not only the tree’s future but also your home and family.

We’re Here to Protect San Jose’s Urban Forest

When it comes down to it, proper tree care is more science than guesswork. The biggest mistakes we see—topping, stripping out too much of the canopy, or making flush cuts—all fight against a tree’s natural ability to heal and grow. The goal should always be to work with its biology, not against it.

If you’re standing in your yard, looking up at a massive oak or a tricky limb over your roof and feeling unsure, that’s your cue. Don’t leave the health of a mature tree, or your own safety, to chance.

The team here at San Jose Tree Service & Landscaping has seen it all. We’re ready to bring our expertise to your property, providing the kind of structural pruning and risk evaluations that protect your investment. As a licensed (CSLB #985639) and BBB Accredited company since 2013, we know exactly what our South Bay trees need to thrive.

Our professional tree trimming and pruning services are all about boosting tree health and making your property safer. If you or your team want help understanding structural pruning standards—or need a certified arborist to guide high-risk trimming—San Jose Tree Service & Landscaping can provide educational support and onsite evaluations for South Bay contractors.

Frequently Asked Questions About Tree Trimming

What is the biggest pruning mistake homeowners make?

Without a doubt, the most damaging mistake is tree topping. This involves indiscriminately cutting the top of a tree, which creates large wounds, invites decay, and promotes weak, hazardous regrowth.

How much of a tree can I safely prune at once?

A good rule of thumb is to never remove more than 25% of a tree’s live foliage in a single season. For older or stressed trees, a more conservative 10-15% is much safer and prevents shocking the tree’s system.

What is the best time of year to prune trees in the South Bay?

For most species in San Jose, the dormant season (late winter to early spring) is ideal. However, it’s critical to prune native oaks only in their deepest dormancy (November-February) to avoid the risk of spreading Oak Wilt fungus.

Can a bad pruning job actually kill a mature tree?

Yes, absolutely. While a single bad cut may not be fatal, severe mistakes like topping or over-thinning inflict immense stress, leaving the tree vulnerable to pests and disease that can lead to its death over several years.

When should I call a professional for tree trimming?

You should always call a licensed and certified arborist for any job involving large limbs, trees near power lines, or storm-damaged trees. Their expertise is essential for safely managing complex situations and ensuring the long-term health of your trees.